Ystalyfera - South Wales

- A Sacred Promise

- Bronchitis Valley

- Dangerous Bridges

- Historian Noel Watkins

- Interesting Snippets

- Lost Landmarks of Ystalyfera

- Pantteg Murder

- Storm Damage

- Torrent in Tarreni Colliery

- Ystalyfera Cemeteries

- Ystalyfera Then and Now

- Ystalyfera Town Crier

The Torrent in Tarreni

When ever I am driving back from Pontardawe along the A4067 I always seem to take a glance at the triangle of woodland that tells me I am almost level with the old Tarreni mine, probably because a couple of decades ago I did manage to climb up to those trees, in search of lost canon balls but that is another story. However the other day I had another reason to give it a thought.

In my work on the Cemeteries I had almost completed Plot 4 in Holy Trinity, I just had to find if an obituary existed for a young man who died in 1909 and who is buried along with his parents David and Jane REES. By photographing and plotting the graves, even copying the words transcribed on the headstones, the occupants are really only names on paper. Entering them on to my data base increases my knowledge in that I now have their relationship with other members of their family and today I am no longer surprised when the list of brothers and sisters runs past no 11th child etc, especially in those earlier years. I really never know when, what or if I will discover anything relating to their lives especially as they died so long ago but sometimes I do find unfortunately in death they did make the headlines.

It is when I find the obituary attached with a date for an INQUEST as in this case, that feelings begin to kick in and by the time the file is finished and added to the others, the grave is no longer only a plot number. It has become the final resting place of person or persons who once lived in the community trying to make ends meet, a family who I have as it were have had the privilege of looking into their lives although very briefly and I am left with a real awareness of what emotions must have been running through that family when the news of yet another injury or death chose to knock on their door.

Thus as stated, my interest in this line of research was originally to discover how the son David Edward Rees, at the early age of 18, had simply met his death. The inquest confirmed that this David Edward was in fact the David Edward who had been one of the victims of the Tarreni Flooding. The following is an entry of the Inquest (which I have condensed to show the relevant details) and the second, a report of the Inquest held in December 1909 (which I have again condensed in fact, cut to show the verdict) I have also included UNDER FOOTNOTE an article I spotted in a November issue.

PLOT 04 Row 04 Grave 11 was at first sight telling of a death of a son aged 18 years of age.

In fact it transpires that David Edward REES died in an accident in Tarreni Colliery. Not the first casualty from mine accidents that I have recorded and until I have completed all plots in the cemetery I dare say not the last but it was the story relating to the accident that brought the disaster to life.

From the Labour Voice, 6th November 1909

DESCRIBED BY MEN WHO WERE THERE

Following as it did, hard upon the Deri and Penrhiwceiber disasters, the flooding of the Tarreni Colliery on Monday caused consternation throughout the South Wales coalfield. For the third time within a week a sense of the terrible toll which modern industry exacts from the workers has been borne in upon us. For the third tome in succession, the heroism, the unselfishness of the miner and his readiness at imminent peril of his own life to succour a stricken mate has stood out as the one bright spot that illumines the tale of death and injury.

In our Welsh columns the circumstances of the accident and a detailed sketch of the workings are given by a correspondent who has direct knowledge of the colliery.

The mad rush for life through the swirling waters, the many deeds of stirring heroism, the care of the strong for the weak, are graphically described below by men who were in the midst of it. These simple recitals of experiences, given to our representative, in terse, unadorned language by men who, only a few hours before were battling for life in the semi darkness, have an interest and pathos all their own. They go to show that beneath the rugged quartz of natures such as those of Tom Owen, there lies a vein of pure gold.

In response to a request from a “Llais Llafur” representative to describe his experiences one of the rescued men said:

“I worked at no 4 East Level. When I was called by Mr Evan Davies, the fireman, I immediately set out with the other men to find my way to the bottom of the pit.

But before describing my own experience perhaps I should explain how I came to be called by Mr Davies. He was standing at the bottom of No 2 West Level when he heard an unusual sound. Thinking it was a journey running wild he paid slight attention at first. But in a short while he noticed the rush of water and instead of running for his life, as 99 men out of a 100 would have done, he followed the water and rushed through it to the bottom of the works making a circuit of the working place and warning all the men.

This I consider a heroic deed and although I do not know much of the conditions attaching to those medals for heroism in mines awarded by the King, I think that if ever there was a brave action underground that deserves it, that Mr Evan Davies is one.”

“To return to my own experience then: When I was warned by Mr Davies we that worked at the very bottom rushed out to the main “bully” or slant. We waded through the rushing water until we came to a certain door. Of that terrible rush to the door I have only a very confused idea: timber, feed bags, sleepers, harness and other things were carried down by the water and we had all our work cut out to keep out of their way. Even on flat ground the water was up to our knees. A horse was fastened to a tram and we passed it. Perhaps it was cowardly to do so, but we had lost our heads.

Well as I was saying, we got to the door and tried to open it but failed. If we had succeeded in opening the door and that volume of water which had accumulated behind it came down upon us, we would have been dead men everyone. So you see it was very fortunate fur us we failed.

AS some of us were pushing and straining to open the door, one of the men shouted: “Chaps, let us go up Edgar Rees’ bully.” This we did. Going through the airway we had to creep on our hand and knees over stones and under them, over falls and between posts. Don’t forget to put down that it was an AIRWAY (this with significant emphasis). It was in a deplorable state and getting through it was the worst experience I have had in many years’ work underground. After getting through this horrible place we crossed the air bridge and to get from there to the bottom of the shaft was an easy matter.

Another man said:

“In No 3 East Level we were apprised of the danger by Me Evan Davies. We rushed to the main bully and there our real struggle began. We had to fight from the very bottom of the point where all the force of the inrush was gathered. As soon as we knew of the danger our first thought was of THE BOYS and we took care to get them all in front of us. At this point all who worked in the district met. We had a fearful fight upwards, through a rushing stream which took away stones, timber, rails etc. and swept them down on us. Many of the big, strong men were almost stunned and fell downwards into deep holes. They were lifted up by those of us who were free to do so. Some of us received electric shocks from cables or wires which were torn from their fixtures and strewn across the roadway. Personally I have no doubt that some of the deaths are attributed to electric shocks. Many of us too were badly burnt.

“At the bottom of the slant where the men first met, Evan Evans received an electric shock which made him almost helpless. He was instantly carried back by the water. Some of the men with me, although nearly exhausted by their struggles, did their best to help him up again, but failed. He then WISHED US GOODBYE. But Tom Williams and Sam Jones the over man, after a hard struggle, succeeded in bringing him to safety.

“There were many other instances of this kind in that awful darkness. We helped each other and the boys; the boys in their turn shouted encouragement to each other. Some were knocked down by the water, carried a distance, then caught and put on their feet. This happened again and again. Several times in the faint light I saw men and boys in difficulties, who could not speak but implored mutely with their eyes.

“I can not possibly describe all the things I saw. One man, Evan Jones, actually carried his boy all the way to a place of safety. John Davies and a few other colliers succeeded in bringing up 6 or 7 boys with them. A young man, Harry Smith, sustained AN ELECTRIC SHOCK and was literally dragged through the torrent by his (butty) Edgar Rees, and another collier David Michael Rees.

“The case of Evan Roderick also deserves a mention. He was weakened by an electric shock but assisted many men and boys in the fight upwards. At last he collapsed and we had to carry him in an unconscious condition.

“Tom Owen, a haulier, who had timely warning from another haulier, disregarded it, thinking possibly that his mate was playing a joke on him. He went to fetch another tram of coal, and returned to the lower double-parting with the tram. When he got there he found water was rapidly accumulating. He did not get excited though, but coolly took the tackle off his horse and put it on the way to return to the stable. You see that the haulier, who is supposed to be a rough UNPRINCIPLED KIND OF MAN, who treats his horse with cruelty, at least thought of the animal’s life when his own was in danger.

“Tom, then found the stream too swift for him to wade through, and he had to return making a circuit of the stalls. On his way he met a boy who was unconscious. He lifted him on his back and carried him all the way.

“At the entrance to no 3 East Level he met a father trying desperately to release his son from rubbish which was pinning him down. He stopped and assisted in getting the boy free.

“There is just one other matter I should like to mention:- A few of the men did not return to the surface who had fought desperately to get out till late that night. Many of the men earlier in the day returned to take part in the work of carrying the dead bodies of their fellow work men from the bottom of the slant, and exploring the mine. Some papers have been generous in their compliments to persons who returned to the pit top elaborately dressed. I think honour should be given where honour is due, and all those who acted in an unselfish spirit whatever their station or position, should be recognized.”

SCENES ON THE SURFACE

One of our correspondents writes:-

Directly the news of the accident became known, the pit surface was the venue of remarkable and unusual scenes. From far and near came men, women and children, some with blanched faces and sinking hearts, fearful for the safety of the loved ones below, all eager for some tidings. Women from Godre’rgraig with commendable foresight brought with them from their houses tea, spirits, and all the stimulants they could think of, ready for those who should come up from the mining constituencies. Clothing of all kinds were brought from the houses, and judging from the pile of shirts, stockings etc, I was privileged to see in the weigh house, there must be many a depleted wardrobe in Godre’rgraig. There was no stinting. Every one was ready and eager to give everything possible to help make the exhausted and drenched men coming out of the mine comfortable. One publican sent down all his available stock of stimulants, sending even the most costly that he had in his cellar.

I was told – but am not prepared to vouch for the truth of this – that two ladies, touched by the sight of a half perishing man coming from the cage, divested themselves of some of their garments in order to clothe him.

A medical man whom I learned later was Dr Daniel, arrived with his wife in a motor car. Mrs Daniel willingly gave away the rug that she had in the car, while Dr Daniel descended the pit and tried artificial respiration on some of the bodies.

I do not think it is generally known that William Lewis, Chemical Row, did not come up until late at night. Regardless of his own drenched condition he stayed down trying artificial respiration and helping the work of rescue. A trained ambulance man, he made good use of his knowledge and once again demonstrated what has been proved time and time again, the value to miners of some knowledge of ambulance work.

In all Godre’rgraig, there was not a resident but was prepared to put his house at the disposal of patients, and not least in their gratitude to them are the men treated so kindly at their hands.”

From the Llais Llafur, November 1909

THE INQUEST

LONG ADJOURNMENTS

The inquest on the bodies of Ben Griffiths (18) and David Edwards (17) two of the victims in the Tarreni Colliery disaster, was held at Ystalyfera on Wednesday by Mr Glyn Price coroner, Mr David Randall (of the firm Messrs Randall, Saunders and Randall) appeared on behalf of the Miners’ Federation. ………

Mr David Rees gave evidence of identification of his son, Edward Rees. Questioned by Mr Randall, he stated that the lad’s face was marked with scratches. The Coroner adjourned the inquest until December 16th when it will take place at Jerusalem Vestry, Ystalyfera.

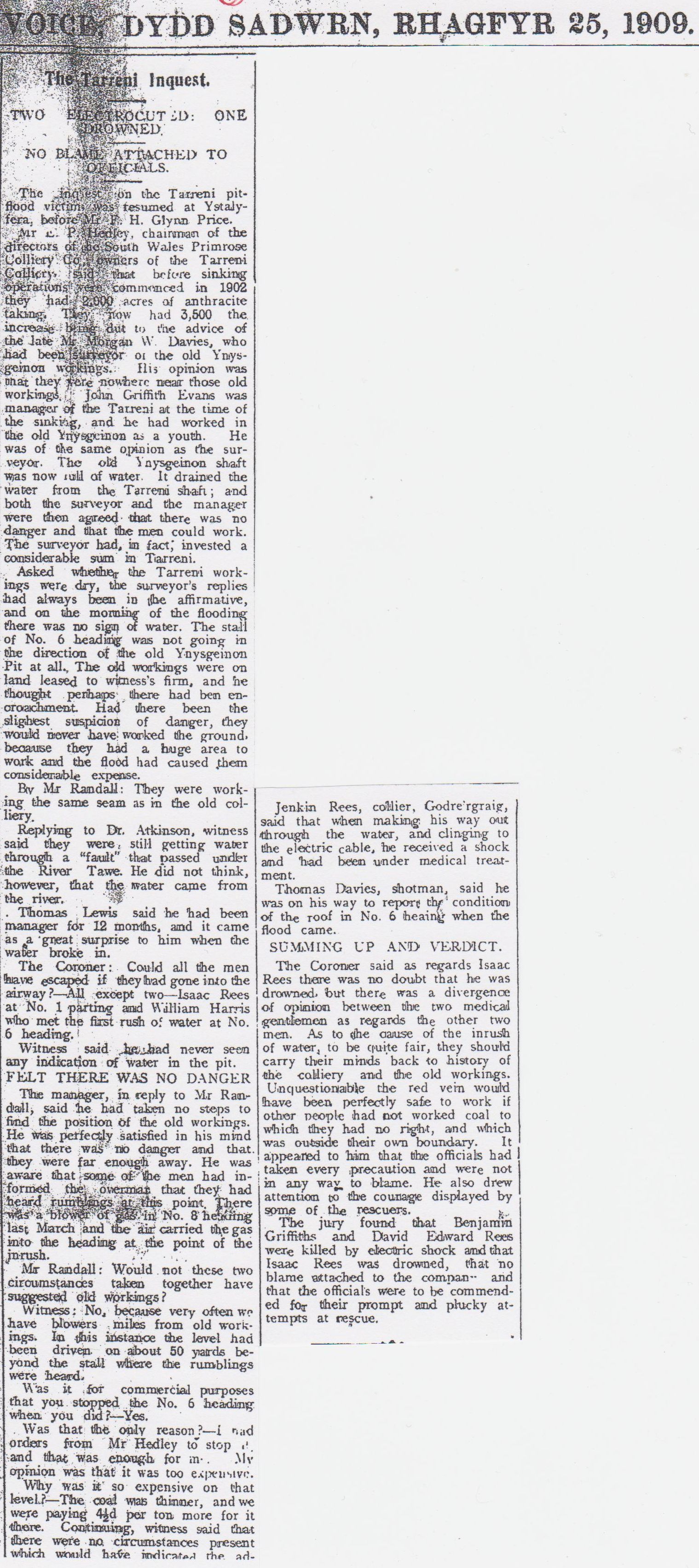

From the Llais Llafur, December 25th 1909

THE TARRENI INQUEST

TWO ELECTROCUTED: ONE DROWNED

NO BLAME ATTACHED TO OFFICIALS

“Mr Hedley, chairman of the directors of the South Wales Primrose Colliery Co., owners of the Tarreni Colliery, said that before sinking operations were commenced in 1902 they had 2,000 acres of anthracite taking. They now had 3,500 the increase being due to the advice of the late Mr Morgan W. Davies, who had been surveyor of the old Ynysgeinon workings. His opinion was that they were nowhere near those old workings, John Griffith Evans was manager of the Tarreni at the time of the sinking and he had worked in the old Ynysgeinon as a youth. He was of the same opinion as the surveyor. The old Ynysgeinon shaft was now full of water. It drained the water from the Tarreni shaft; and both the surveyor and the manager were then agreed that there was no danger and that the men could work. The surveyor had in fact invested a considerable sum in Tarreni.

Asked whether the Tarreni workings were dry, the surveyor’s replies had always been in the affirmative and on the morning of the flooding there was no sign of water. The stall of No 6 heading was not going in the direction of the old Ynysgeinon Pit at all. The old workings were on land leased to witness’s firm. And he thought perhaps there had been encroachment. Had there been the slightest suspicion of danger, they would never have worked the ground because they had a huge area to work and the flood had caused them considerable expense...

SUMMING UP AND VERDICT

The Coroner said as regards Isaac Rees there was no doubt that he was drowned but there was a divergence of opinion between the two medical gentlemen as regards the other two men. As to the cause of the inrush of water, to be quite fair, they should carry their minds back to history of the colliery and the old workings. Unquestionably the red vein would have been perfectly safe to work if other people had not worked coal to which they had no right and which was outside their own boundary. It appeared to him that the officials had taken every precaution and were not in any way to blame. He also drew attention to the courage displayed by some of the rescuers.

The jury found that Benjamin Griffiths and David Edward Rees were killed by electric shock and that Isaac Rees was drowned, that no blame attached to the company and that the officials were to be commended for their prompt and plucky attempts at rescue.

FOOTNOTE:

From the Labour Voice Saturday 13th November 1909

CAUTIOUS ABOUT RESUMING WORK

Work will be resumed at the Tarreni Colliery on Monday. Meetings of the men have been held during the week, at which there was keen discussions on the report of the men’s representatives who examined the Ynysgeinon workings. Conditions it appears were not all that the men desired, particularly in the matter of drainage; and they were determined upon every possible precaution for their safety being taken before returning to their work.

Some dissatisfaction was also expressed at the personnel of the jury, which they allege, is made of publicans, insurance agents, tradesmen and others who have little or no acquaintance with underground work. They feel that persons serving on the inquiry should have a full knowledge of work in a mine.